The Long Modernization of the Italian Railways

Why High-Speed Rail is not the only modern rail.

Since I was a kid, I felt that railways without overhead electrification were “incomplete” or “primitive.” I can’t quite explain the feeling, but growing up in the 1980s, my grandpa regularly brought me to watch the trains pass through the station of San Ruffillo along the Direttissima Bologna-Firenze, where freight, diretti, espressi, accelerati trains whooped by every few minutes along what was at the time one of the busiest sections of the Italian rail network. I didn’t realize it then, but the Direttissima was the epitome of a “modern” railway of its time: electrified, fully grade-separated, with low grades, large radiuses, long tunnels and arched viaducts, well-designed stations with long platforms and pedestrian underpasses, straight tracks and lateral passing loops to allow swift overtaking. Shortly, everything a railway at the time needed to offer more capacity, higher speed and better operations. Used to this lavish infrastructure, the local diesel-powered railways with low platforms, barebones stations, and outdated signalling that were still common in many parts of the network back in the late 1980s felt like archaic things from the past to my kid’s eyes.

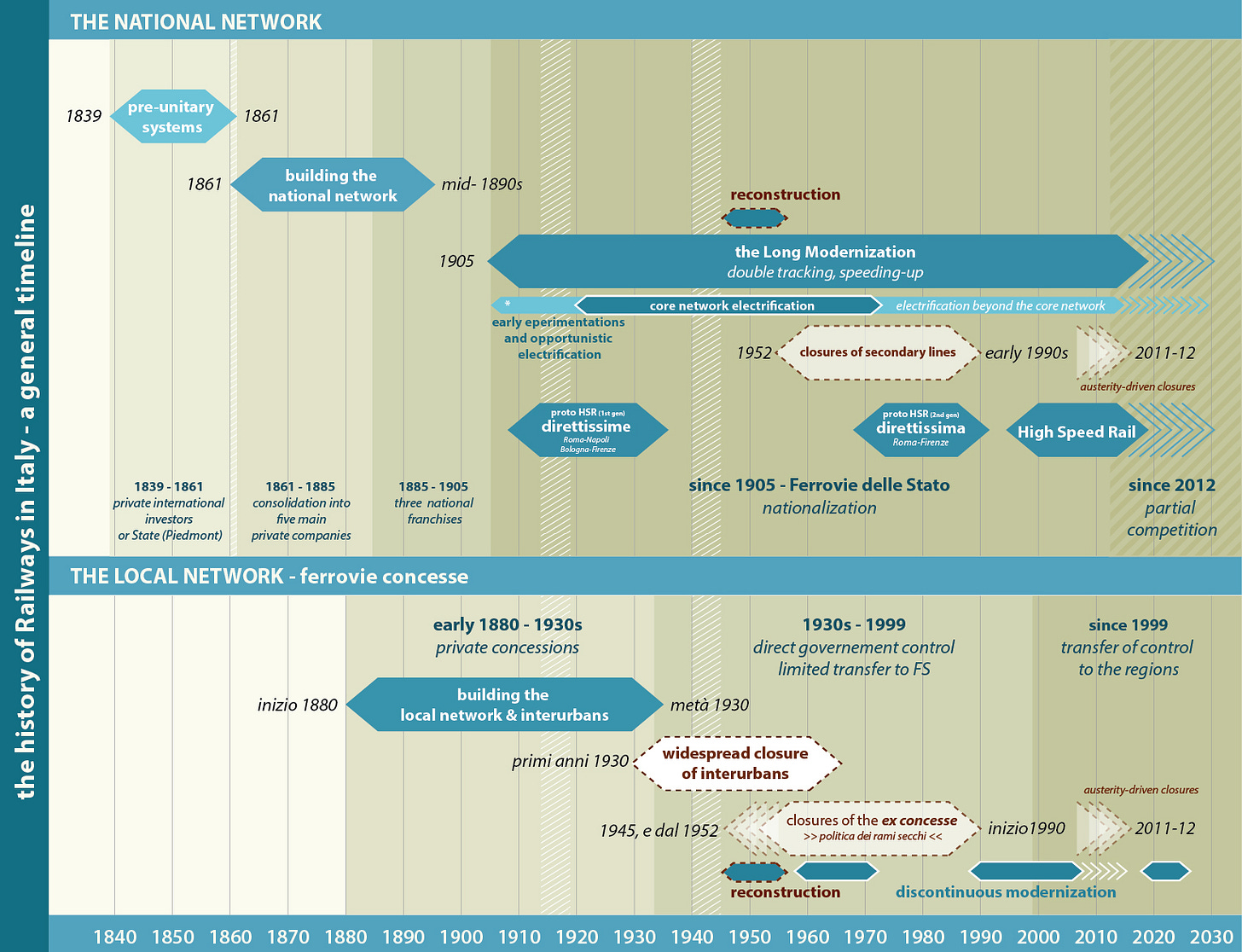

This post aims to be an overview of the century-long process that, for lack of fantasy, I will call “the Long Modernization.” Modernity is a slippery, vague concept that should be used cautiously. Still, it is the best one I can think of to convey the idea of a long process that took the railway infrastructure of the 19th century, built for fewer passengers, slower trains, lower line usage, overall a more labour and energy-intensive endeavour, and progressively delivered a core national network that was capable of handling more traffic, faster and more safely, thanks to technological and infrastructural upgrades to its fixed and mobile infrastructure, encompassing every aspect of the railway: signalling, electrification, the permanent way, realignment and double-tracking of lines, civil structures, stations, grade-crossing removal, reorganization of entire urban nodes, including the High-Speed lines of yore, the Direttissime, and those of today, the AV/AC lines. This process of continuous upgrades, which started at the dawn of the 20th century with the nationalization of most of the railway network and is still ongoing, has delivered a railway that is far from perfect but provides the country with affordable and far-reaching rail passenger service, in a way many developed wealthy countries on my current side of the Pond can only dream of.

Nationalization as the prerequisite of modernization

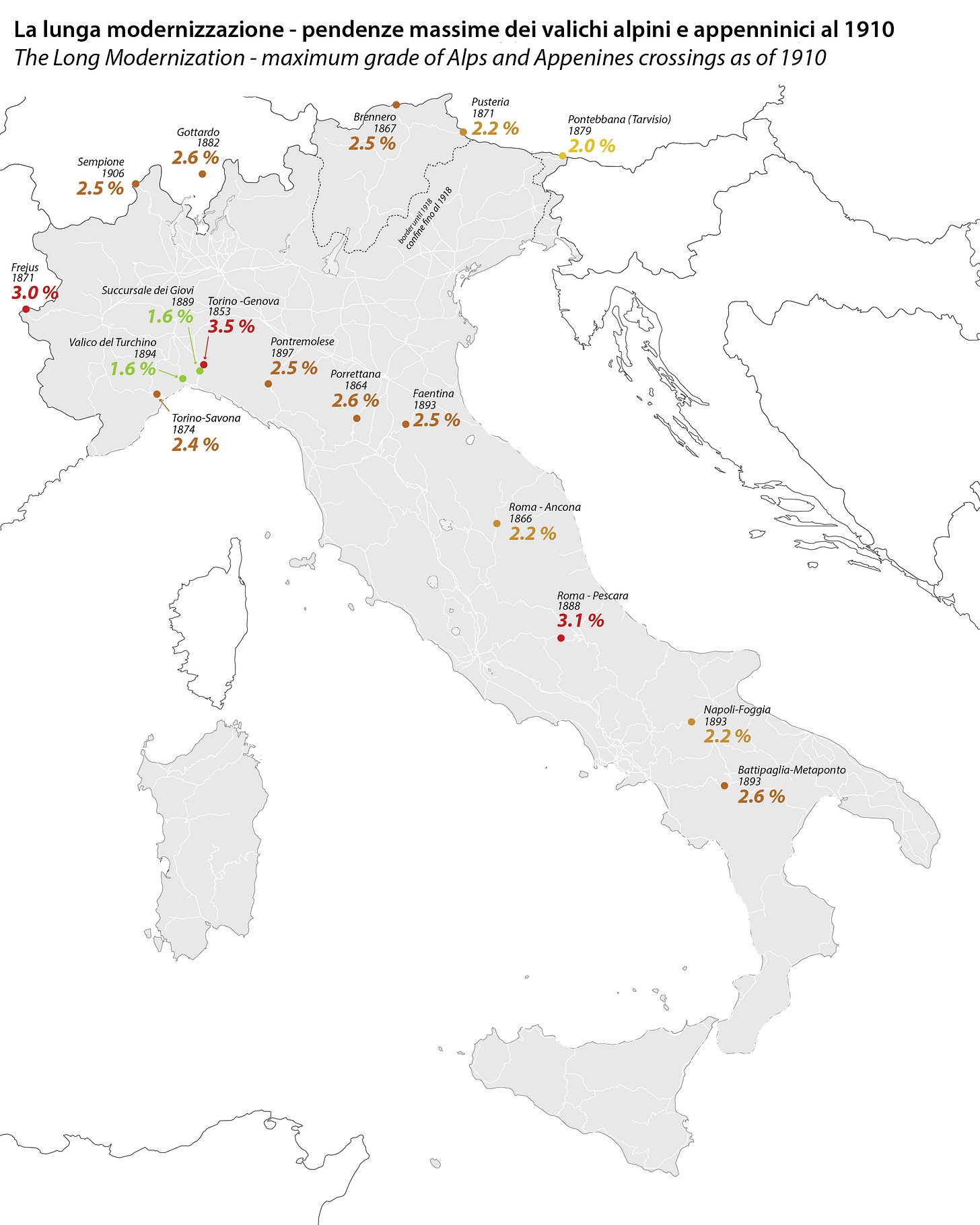

This process of progressive improvements of the railway infrastructure via technological innovations and investment is not exclusive to Italy. It’s a common path followed by many countries during the 20th century (but abandoned by many others). However, this process is probably more evident in the Italian railways than in Western and Central European peers because the starting point at the dawn of the 20th century was a railway network developed on a tight budget, trying to stretch limited resources to build a comprehensive national network as part of a broader nation-building effort, even where lines didn’t make a lot of economic sense at the time. The result is a rail network that by the early 1890s was covering most of the nation but was built to suboptimal standards: single-track curvy lines with steep grades even on major trunk routes, with many lines constructed to handle a maximum axle load of just 15 tonnes, limiting the power of locomotives and the lengths of trains.

The network that the newborn Ferrovie dello Stato inherited from the three private concessionaires in 1905 urgently needed significant, continuous, and coordinated investments to support Italy's first real industrial take-off that started in the late 1890s. This was an investment that the private concessionaires were unwilling or unable to make, so the government, led by the liberal Giovanni Giolitti, pushed for nationalization in the early 1900s, considering that only the power of the State could undertake this gargantuan effort.

1905 can be considered the starting point of the Long Modernization, despite some early isolated examples, like the already cited Succursale dei Giovi happening at the end of the 19th century. However, it was only after 1905 that many projects discussed since the late 1880s finally became more concrete. The construction of the Direttissime Roma-Napoli, approved by Parliament in 1905, and the Bologna-Firenze, approved in 1908, the reorganization of the node of Milan initiated in 1906, and several double-tracking projects that stagnated for years under the reign of the three concessionaires were given a first decisive impetus thanks to the nationalization. This effort, which was slowed down by the Great War and the subsequent economic crisis and political turmoil of the early 1920s that led to the collapse of the Liberal Era and the ascent of fascism, regained strength in the second half of the 1920s and the 1930s, with the extensive electrification of the core network, the reorganization of major railway nodes and reconstruction of major stations, the renewal of rolling stock and the progressive adoption of more modern signalling. It was stalled again for more than a decade by World War II and reconstruction. It again gained momentum in the 1950s as the Italian economy took off during the so-called Economic Miracle and has continued uninterrupted until now.

In the following sections, I will discuss a few elements of this Long Modernization in greater detail, such as right-of-way upgrades, station modernization, overhaul of urban nodes and level crossing removal. I will not spend much time on electrification, which I covered in a previous post. I will only briefly talk about signalling and rolling stock, topics that are as important for the modernization process and equally interesting but that I’m less familiar with.

More tracks, faster tracks – the figures of right-of-way modernization

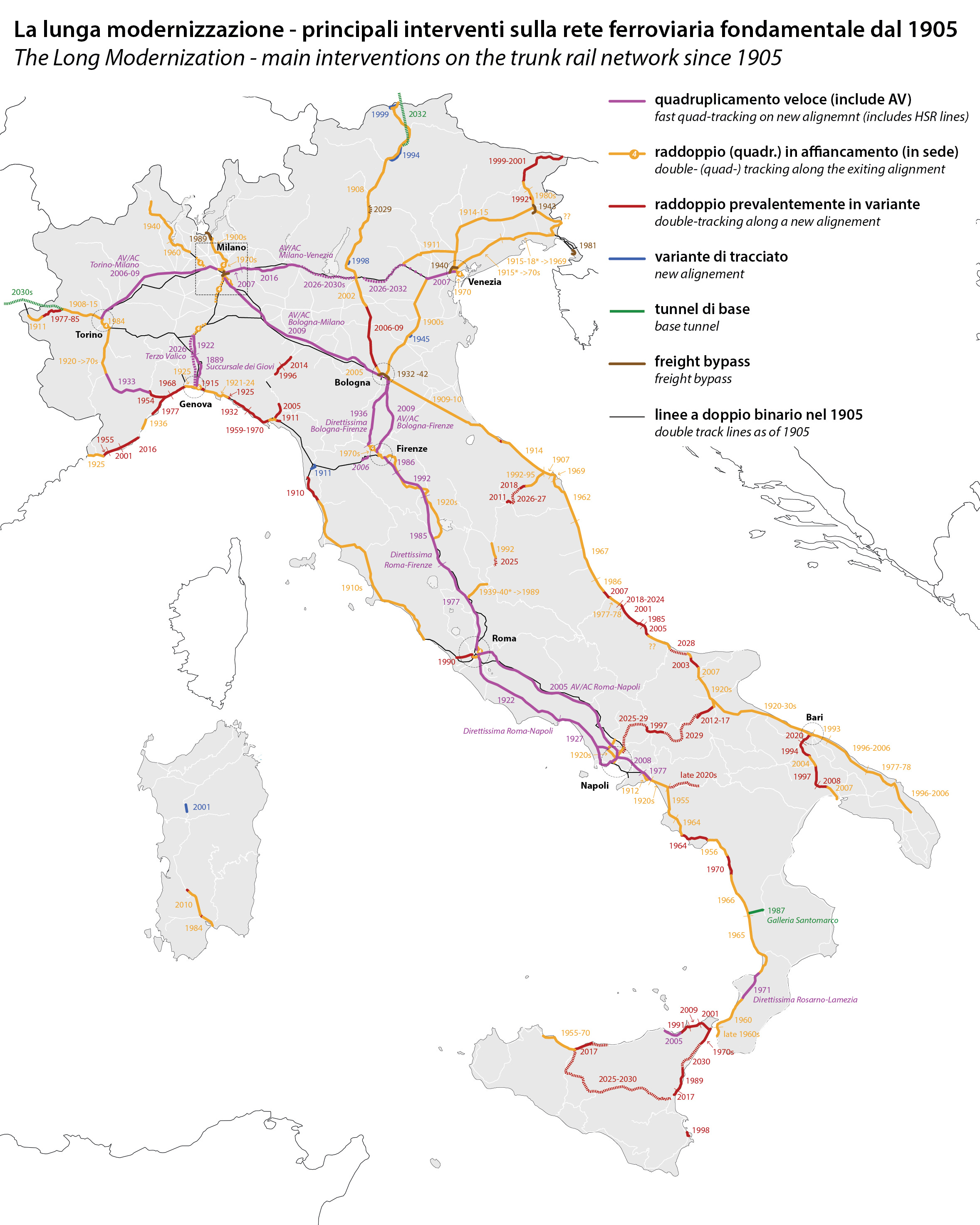

One of the most visible elements of this continuous modernization is the improvements in the performances of existing trunk lines, which was achieved thanks to double- and quad-tracking to add capacity, coupled with the rerouting of long sections of existing lines along straighter alignments, the construction of bypasses and base tunnels, and other significant changes in the railway’s right-of-way intended to rise the maximum speed by reducing grades and increasing the curves radiuses. This prolonged effort ended up producing an entire vocabulary of planning terminology that has entered the railway planning jargon and can be found in most planning documents, which I will summarize below.

Raddoppio (quadruplicamento) in affiancamento/in sede – double- (quad-) tracking along the existing alignment.

This is the simpler case, where a second track (or several tracks) is laid alongside the existing ones by expanding the embankments, cuts, or bridges where the existing track already is. This method was generally used in relatively flat and less populated areas with room to add additional tracks without extensive demolitions and disruptive civil works, where the existing geometry allowed higher speeds. It’s also more prevalent in the earlier days of modernization, characterized by a less NIMBY attitude toward infrastructures among the population and lower spending capacity.

The “raddoppio selettivo” or partial double-tracking is a sub-typology and a less common occurrence that has become more popular recently as part of an effort to better fine-tune infrastructure improvements to schedule planning, especially on secondary passenger lines that host moderate regional traffic with both local and express service.

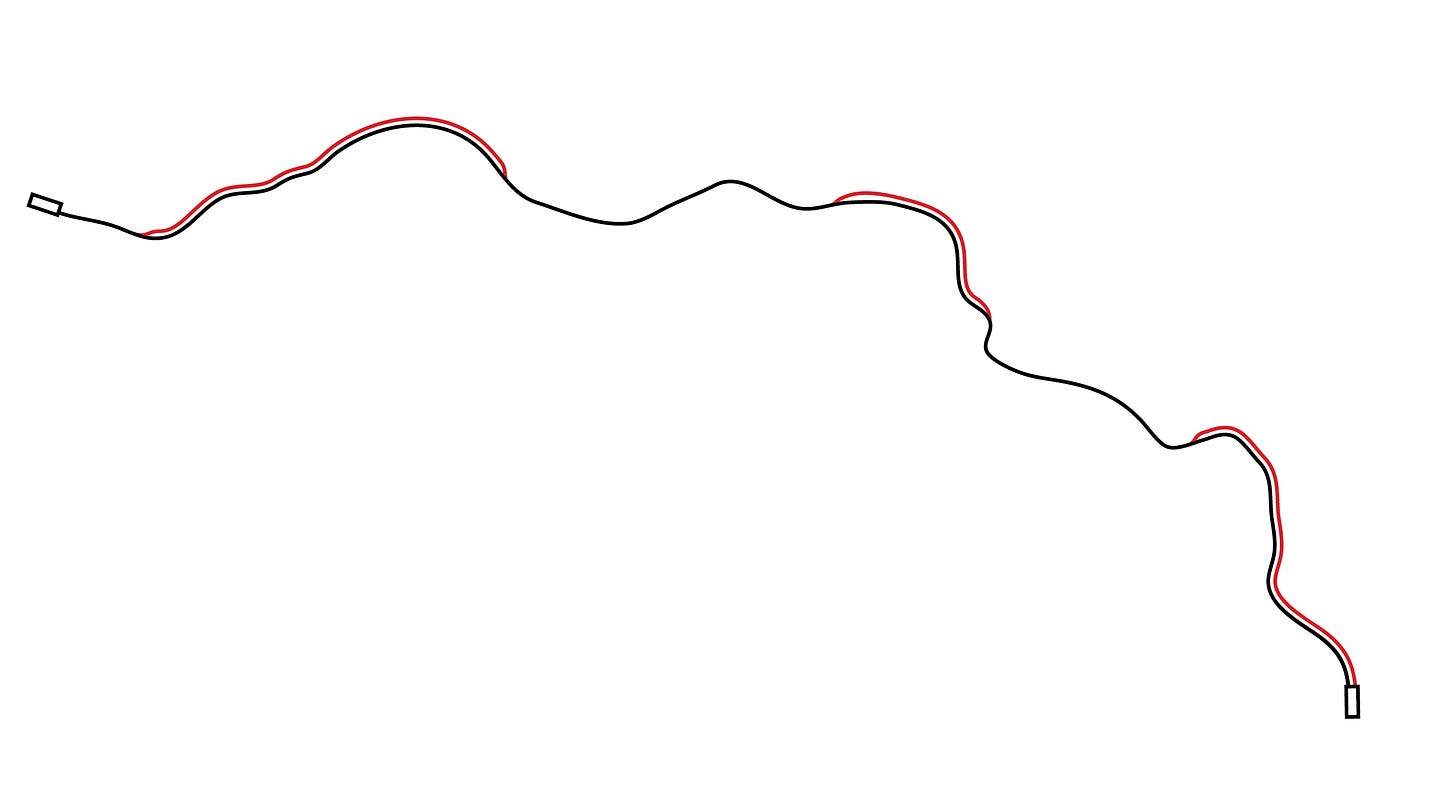

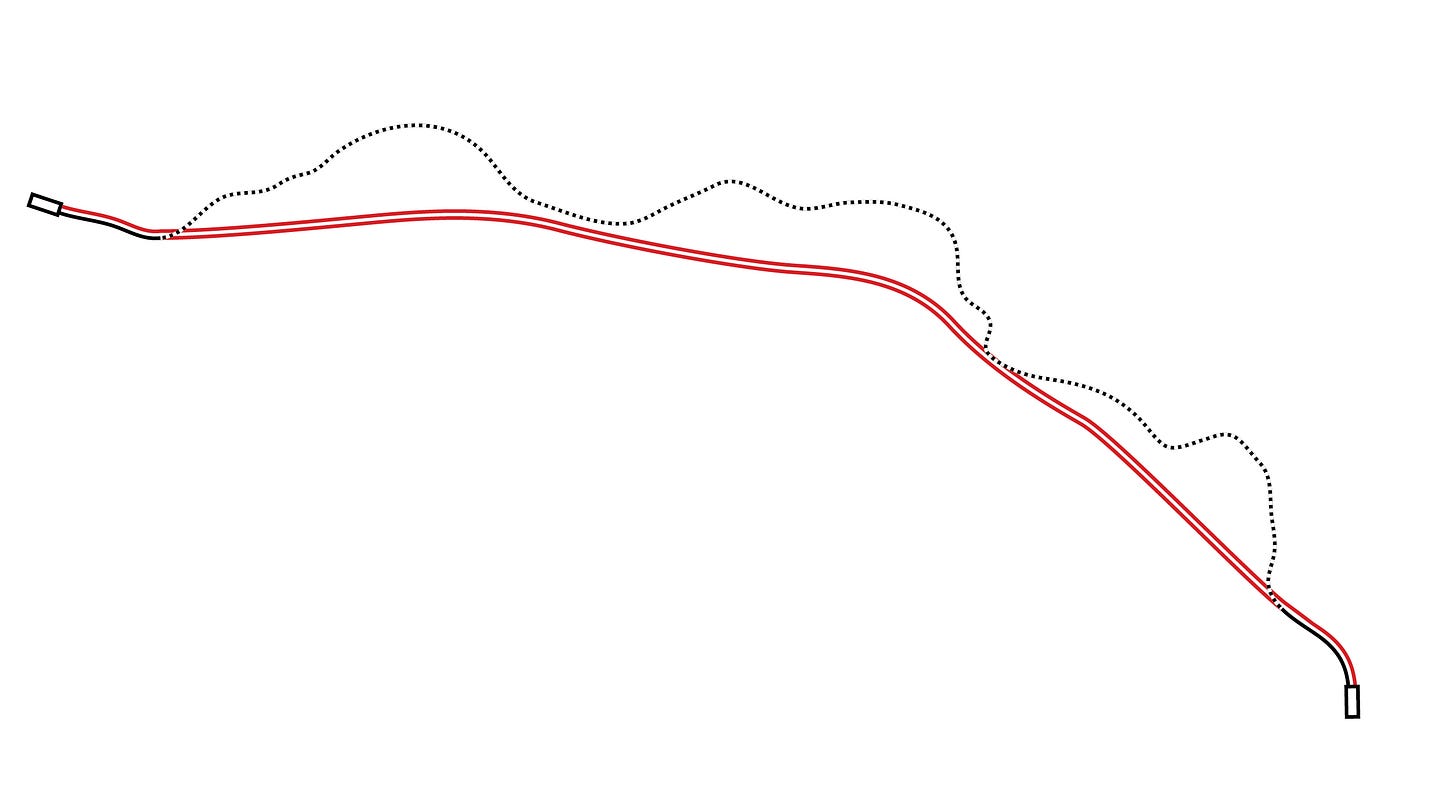

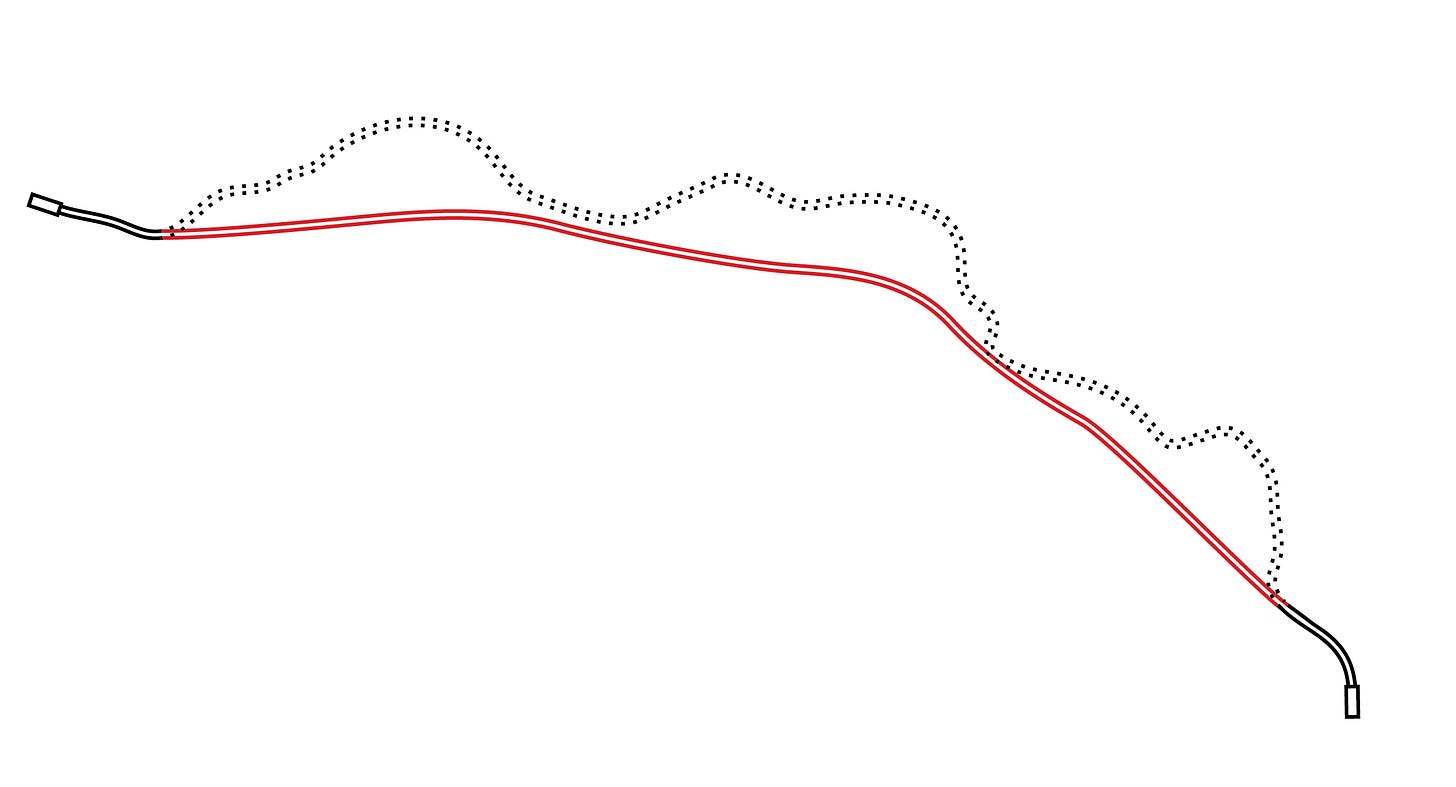

Raddoppio in variante – fast quad-tracking along a new alignment.

Double tracking along a new alignment is the prevalent approach when the goal is to achieve higher capacity and higher speed or bypassing a geologically unstable area, a recurrent problem in the hydrogeological fragile Apennines, or one prone to flooding. The old single-track alignment is totally or partially abandoned, and a new two-track, straighter alignment is built. This often involves extensive civil structures, such as viaducts and tunnels, as this approach is common in mountainous areas, such as the rugged Ligurian and Calabrian coasts, or in the heavily urbanized and flood-prone ones, such as some parts of the Po Valley and the Adriatic Coast.

Variante di tracciato – new alignemnt

The realignment of an existing portion of a single- or double-track line without increasing the number of tracks is generally referred to as “variante” or “variante di tracciato.” This approach is usually preferred when the main goal is to achieve higher speed, bypass geologically unstable or flood-prone areas, or, unfortunately, more and more frequently in recent NIMBYer times, push the railway outside of built-up areas where it is often considered a nuisance by local notables.

The lighter, more targeted version of this typology is the “rettifiche di tracciato,” i.e., localized straightening. This term refers to surgical interventions on limited segments of a line to smooth its geometry and achieve marginal gains in speed.

Tunnel di base – base tunnel

This is probably a more commonly known figure of right-of-way modernization. Base tunnels are needed to replace mountain lines with steep grades and tight curves, offering a so-called flat route across mountain ranges for freight trains, reducing the need for additional traction power. The most famous examples are the Gotthard and Ceneri base tunnel and the under-construction Brenner, Frejus (Mont d’Ambin), Semmering base tunnel.

Quadruplicamento veloce – fast quad-tracking along a new alignment.

Fast quad-tracking is the term generically used to identify new trunk lines that double existing mainlines along a new alignment built for higher speeds. Both the Direttissime and the Alta Velocità/Alta Capacità (AV/AC – High Speed/High Capacity) are often referred to in planning documents as “fast quad-tracking,” stressing the two main reasons why this radical, costly intervention was considered necessary for some corridors. First, they substantially increase capacity by separating fast and slow traffic, going from a situation of “circolazione eterotachica”, an Italian planning jargon term for mixed-traffic operations, to one of “circolazione omotachica”, where fast and slow traffic is separated on different lines. Secondly, it also permits higher top speed for intercity passenger traffic, which is not necessarily the main advantage of building a High-Speed line (or a passenger-dedicated line in Chinese planning jargon) even though it is often the most shiny and politically visible.

The following map provides a visual overview of how these different figures of right-of-way modernization played out since 1905 across the trunk rail network. The choices between the different strategies depended on the main planning goals, political will (or lack thereof), available resources, specific local conditions and the evolution of the local population's attitude and notables toward the railway, which is increasingly pushing the rail away of built-up areas or underground. This trend is visible almost everywhere throughout the peninsula, especially in Southern Italy and along the coasts. The Ligurian coast is possibly the most striking example, as the more recent “raddoppi in variante” of the Western Riviera are way more inland than the ones built during the interwar and postwar years on the Eastern Riviera. They are pushed away from the beaches and the built-up areas under political pressure, but also because of objective difficulties in building through much more urbanized areas while complying with modern environmental and safety requirements.

An attentive look at this map tells the story of how switching priorities and available resources have shaped the Long Modernization: the hastily done and then dismantled double-tracking on the eve of the Great War on the North-Eastern front, only rebuilt for good in the postwar years; the effort of balancing investment on lines with high demand, such as the lines radiating from Genoa to the industrial powerhouse known as the “Industrial Triangle” at the beginning of the 20th century and the North-South main spine later with the political will of keeping investment flowing also toward more marginal areas for territorial equity (and electoral interest); the rise of commuter traffic around the main urban nodes starting from the 1960s pushing the need for quad-tracking; The increasing dominance of “raddoppi in variante” rather than “in affiancamento” as the country grows wealthier and hence NIMBYer.

However, this map also testifies to the main argument of this post, which is the idea of an underlying long-term trend. The Adriatic line is, in my opinion, one of the most glaring examples of the long-term policy perseverance that is the foundation of the Long Modernization: the first segments between Bologna and Ancona were double-tracked in the first two decades of the 20th century, but the full double-tracking between Bologna and Lecce will not be completed until 2028, an effort stretching more than 120 years!

The urban nodes

The reorganization of major urban nodes, which started right before World War I and continued until today, is one of the most overlooked aspects of a functioning modern railway because they often represent significant bottlenecks in the network, severely limiting capacity and regularity. The railway urban nodes of the pre-nationalization era were severely underbuilt. Often, multiple trunk lines converged on shared last-mile congested station approaches. The interwar and immediate postwar overhaul of major urban nodes left the Italian railways with a precious legacy: large stations with a lot of capacity and, even more importantly, a few generous urban right-of-ways feeding into stations were, many years later, it was possible to build urban penetrations of the high-speed lines without excessively onerous interventions, something that the proponents of HSR in Canada, Australia, the UK and US would love to have.

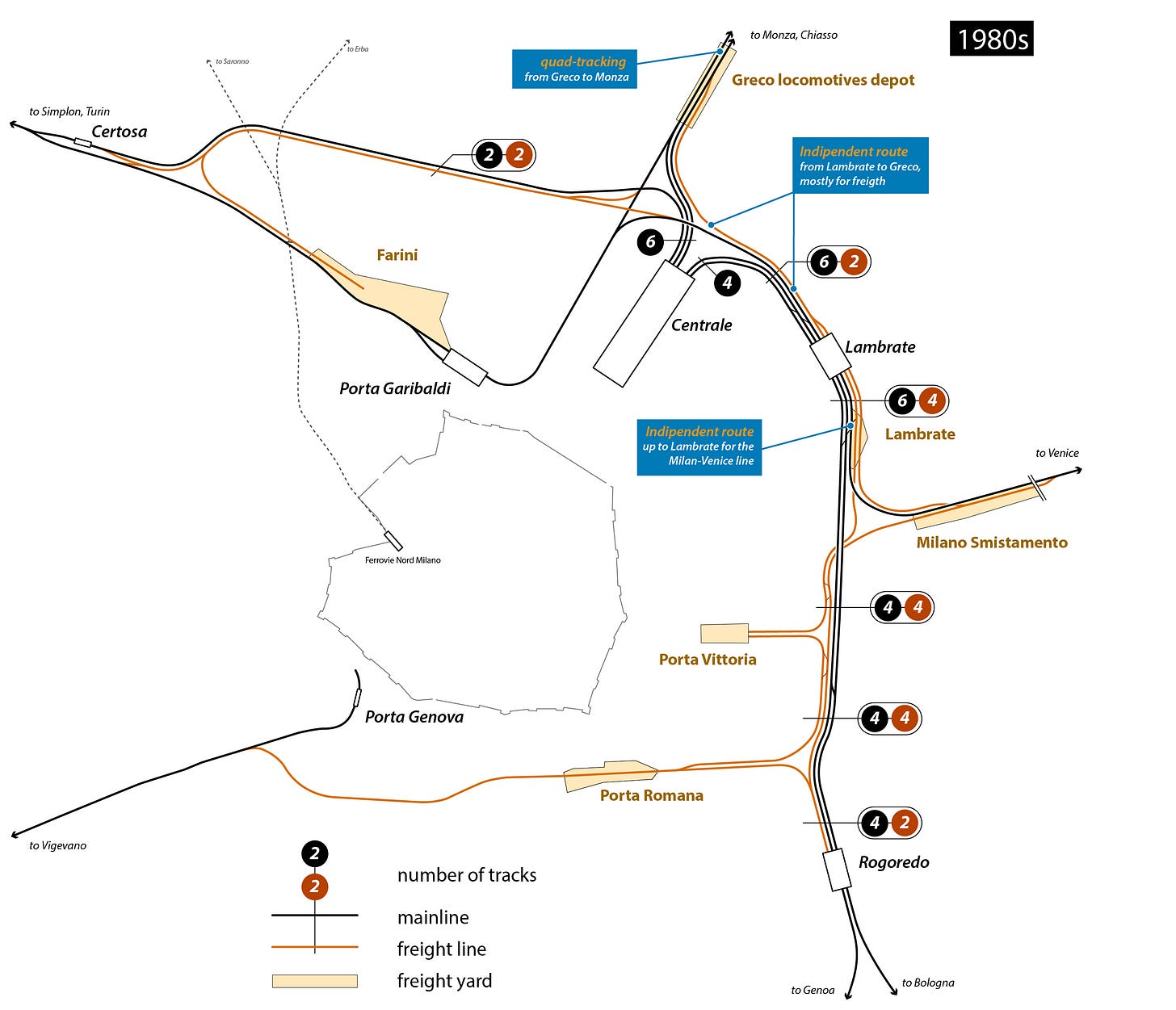

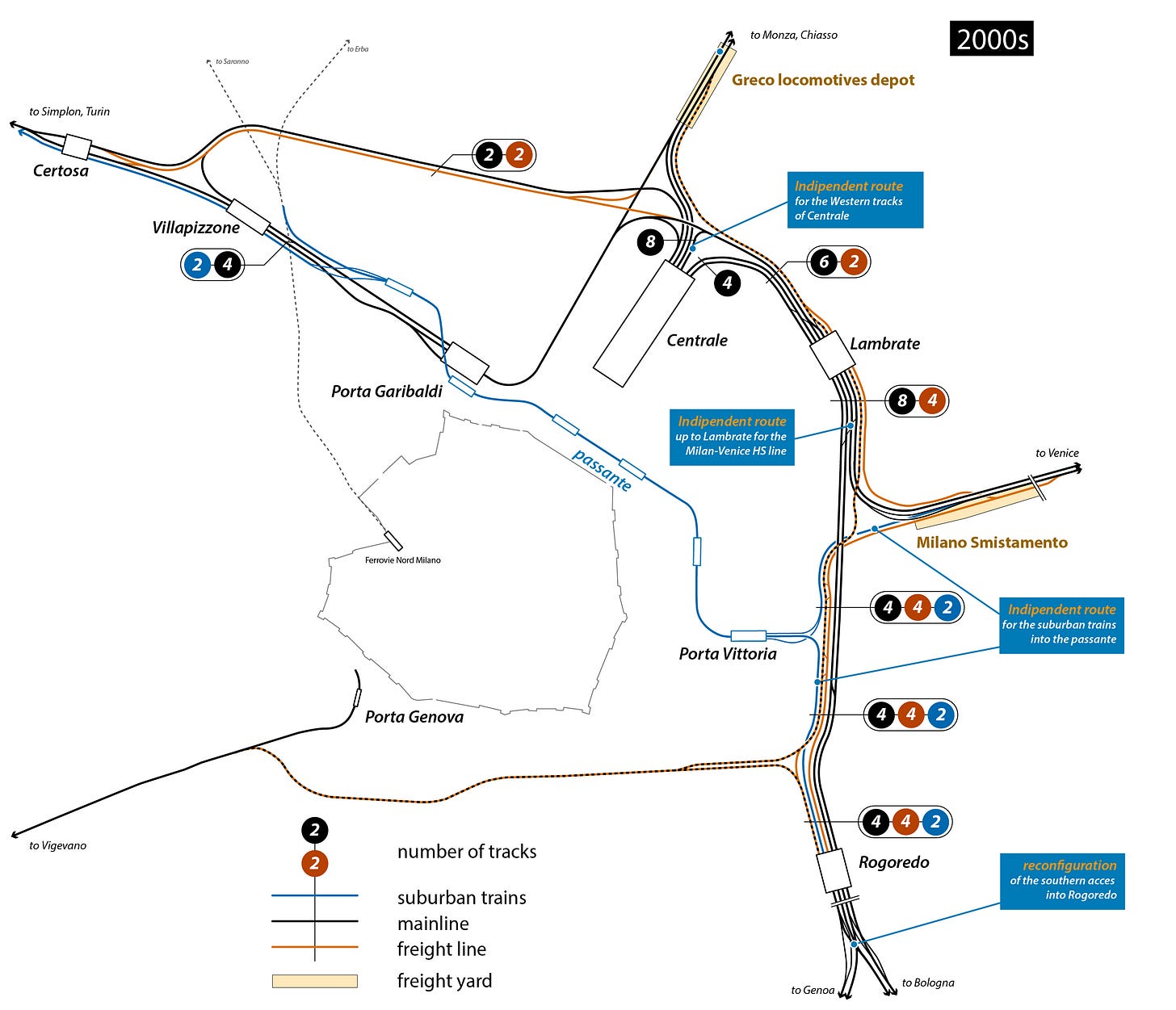

Milan is probably the best example of the progressive growth of urban nodes’ capacity over time thanks to generous rights-of-ways provided by the interwar “urban node reforms”. Until the early 1900s, all the lines converging into Milan from the South and the East shared a common 2-tracks last mile stretch on an arched viaduct leading to the old Stazione Centrale, including freight traffic heading to the freight yards near the station.

When the major reorganization that started in 1905 was completed in the 1930s, four tracks were available for general traffic from Rogoredo to Centrale plus four additional grade-separated freight tracks connecting the major city yards with the new shunting yard of Milano Smistamento without interfering with mainline traffic.

Thanks to the generous right-of-ways and yard space acquired during this reform, it was possible to add additional tracks in the 1960s to separate the Milan-Venezia line from the Milan-Bologna south of Rogoredo and reconfigure the points of conflict to pursue what the FS planning jargon referred to as “itinerari indipendenti”, i.e. giving each pair of tracks converging onto the node its own independent path minimizing as much as possible conflicts and bottlenecks. The effort was pushed further in the 1980s with the reconstruction of Lambrate and the addition of four more tracks in the station and two more south of it for freight and regional trains terminating at Lambrate.

Finally, between the 1990s and the 2010s, with the arrival of HSR and the construction of the passante cross-city railway link for suburban trains, the node was further reorganized with additional tracks, on the Eastern Belt, which now has up to 10-12 tracks on some segments, new grade separated junctions and a complete reconfiguration of the southern access from Rogoredo with four tracks to Bologna (HS and conventional line) and four more to Genoa, in preparation of the planned four-tracking of the entire Milan- Genoa corridor that will happen in the 2020-30s.

The stations

Another main aspect of railway modernization was the gradual but radical change in the structure and experience of stations. Every major station has its own history related to the local urban context, but we can track a general trend: the main 19th-century stations, which used to be made of a few tracks under a cast-iron and glass canopy beside an ornate main building with a lot of service tracks in the precinct and freight areas for city-bund packages (called piccola velocità in Italian rail jargon), were radically modernized in the interwar and immediate postwar period. Most stations grew to more than 20 tracks with better throat layouts and the characteristic art deco (Bologna, Milan) or modernist (Rome, Florence) signal boxes for the centralized control of switches, with fully paved platforms 30 cm above the track, with pedestrian underpasses to avoid track encroachment and generous canopies to shelter the passengers, and new head buildings with modern services for their comfort. Many of these station overhauls weren’t complete until well into the 1950s, when Roma Termini and Napoli Centrale opened in their current form.

Local stations along the trunk lines underwent a similar process of progressive upgrade to follow the evolution of technology, labour organization and costs, and societal expectations about comfort, safety and universal accessibility. The 19th-century station, with its earthen floor low-level platforms with no canopy and its narrow second platform accessible via wooden at-grade crossings, has evolved over time into a station with higher paved platforms allowing level boarding on most trains, pedestrian and bike underpasses with elevators or ramps for universal accessibility, real-time passenger information, but often no on-site personnel, no ticketing office but maybe a characteristic bar della stazione still functioning...

Level crossing removal

Finally, it is worth spending some word on the removal of level crossings. Even if grade-crossing removal is touted by some as “car infrastructure”, grade separation is often necessary to improve railway operations on busy lines because it allows for higher speed (160 km/h is the top speed achievable on lines with at-grade crossings in Italy), and it makes the increase in frequency more socially acceptable is it would otherwise be disruptive to local traffic. The modernization and progressive removal of level-crossing is another emblematic example of the Long Modernization, a slow but constant process. In 1948, there were around 17,500 level crossings along the entire national rail network, mostly manually operated by a casellante, a railway employee living in a small house near the gate, the casello, sometimes operating a few contiguous gates via a system of ropes. In the following years, only a few of them were closed or replaced, but from 1958, the effort gained a bit more momentum, with a mix of grade separations on national roads, closures of low-traffic ones and upgrade of the remaining to automatic operations. By 1967, the number of at-grade crossings had gone down to 14,580. During the 1970s, automation was completed, and in the 1980s, the systematic effort to remove most level crossings on the main trunk lines finally took off thanks to a 10-y plan passed in 1983 by the Parliament, renewed in 1998. By 2000, the number of level crossings had been further reduced to 8,063, and it continued its descent to 4,072 in 2024. Today, most trunk lines are fully grade-separated, increasing top speed on conventional lines to 200 km/h, while more grade separations are in the pipeline as part of a continuous national plan.

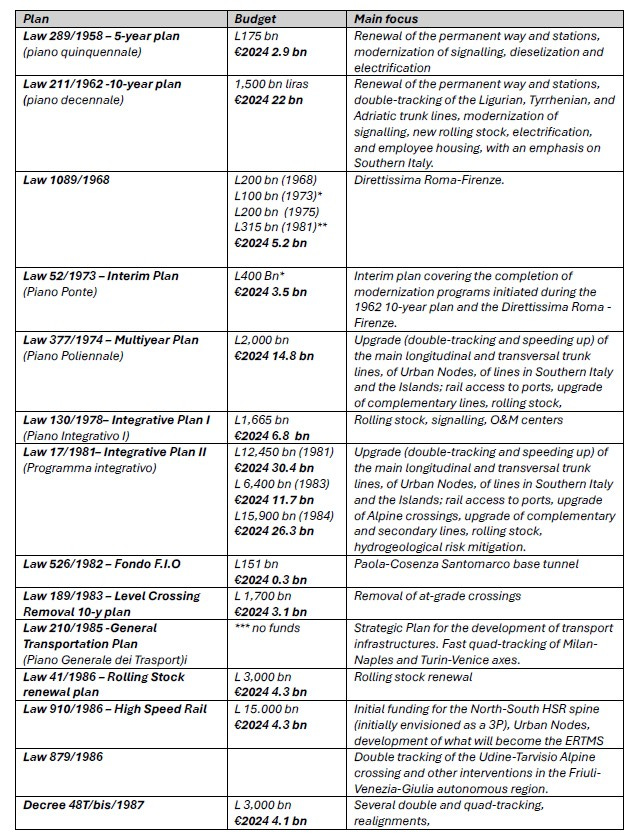

Laws, plans, programs: the legal background of the modernization.

Creating the FS and developing a good structure of in-house expertise has been fundamental to sustaining this continuous modernization effort. But this wouldn’t have been possible without the legal and financial background provided by the national government over the years. Starting in the late 1950s, when North American private railways started to retreat from passenger services, the Italian Parliament passed the first of a series of multi-year plans aimed at improving the railway network, whose reconstruction after the war devastations was just completed. In the following years, many more plans pursued the effort, which was finally systematized in 1991 through the tool of so-called “accordo di programma”, i.e. a multi-year framework agreement between the Italian Government and the FS (RFI – Rete Ferroviaria Italiana since 2001) governing capital spending over a five-year period with yearly updates linked to the budget process. A framework that still governs rail investment today.

This continuity allowed FS and the supply chain of specialized contractors to maintain and increase their expertise in core competencies such as tunnelling and electrification, developing state-of-the-art techniques for box-jacking for underpasses, and standardized design for all the elements of the rail, from sleepers to platform edges, from OHLE to cable conduits to Electrical Substations. This policy and funding continuity has been the fundamental engine behind the Long Modernization that helped FS survive through the 1980s crisis, the Tangentopoli scandals and the various attempts at privatization.

Modernize or die.

Rome wasn’t built in a day, and the Italian railway network wasn’t either. But day after day, law after law, project after project, the Italian railway network was able to keep pace with the changing society's needs and remain relevant despite the competition of the car and the plane. I hope I didn’t give the reader the impression of the Long Modernization as a triumphal Long March toward an inevitable bright future. It was far from this. Outside of the trunk network, modernization efforts have been less consistent. The closure of many local railways and interurban can be seen as the inevitable result of a bifurcation in history that these obsolescent infrastructures faced as their assets were reaching the end of life and technological obsolescence: modernization or closure. Some, where demand was stronger or political will was there, could undertake the path of modernization necessary to ensure their survival. Most of the others were closed immediately or endured a long agony. Moreover, freight rail has been stagnating or declining since the advent of containerization, and only now are there systematic efforts to bring the infrastructure into the era of intermodal freight.

Despite what a recent study claims, Trenitalia is not the best European railway operator, and the Italian railways are by far not the best of the continent. But I think their history offers a few lessons for those countries aspiring to improve passenger railways, notably North American countries that almost completely abandoned intercity passenger rail, such as Canada, Mexico and, to a lesser extent, the US. High-speed rail is a shiny, promising perspective that politicians, media, advocates, and voters love to dream about. And some love to hate. Still, a network of conventional lines connecting more than just the major metropolises at a decent speed achieved via the modernization of the existing network to non-HSR standards is a path that shouldn’t be overlooked, as Mexico seems now to understand. China is building a massive HSR network but is also upgrading its legacy one, which doesn’t get as much attention. India is following a similar path, albeit with more emphasis on the progressive modernization of its legacy network with, among other things, the most impressive electrification program ever undertaken by any country. Countries will take different approaches to improving their railway, depending on their geography, starting point and resources. Many may be tempted to leapfrog to some shiny new tech, real ones, like HSR or Maglev, or imaginary ones, like Hyperloop. And that might be the best choice for them.

If there is a lesson to be learned from the history of the Long Modernization, it is that the railways need to continuously embrace new technologies, practices and planning ideas to remain relevant in today's world and that discreet improvements are as important as multi-billion megaprojects. However, this requires abandoning the project-driven approach typical of the anglosphere and embracing a more old-fashioned but, I believe, more effective State-led approach made of plans, programs and long-term policy commitments.

Bravo! Fantastic work. It’s remarkable what can be achieved when you have slow but steady progress for over 100 years.

I’d be interested to learn more about how incremental improvements like grade separations and track improvements get funded. Are these budgeted out of a general improvement fund, which is relatively consistent over time?

Reflecting on your comment contrasting against Anglo-sphere project planning, I suspect it’s better to have a smaller but long-running, predictable budget than “surprise” big-bang funding.

This is an incredible essay - I love the extremely detailed classification of different types of projects, along with numerous examples. This must have been an enormous amount of work to put together. This is really valuable work, to document all this history in a form that may be more legible to English-speaking planners and policy-makers.