Build trams. But build them well.

Understanding what tramways are, what they do best and how to employ them.

This weekend, Toronto will open a new tramway line, the Finch “LRT”. It’s a brand-new modern tramway with a fully dedicated, exclusive right-of-way and an at-grade intersection. It’s supposed to replace a busy bus and provide “rapid transit on a budget” (well…) in a city that desperately needs more higher-order transit. Surprise, surprise (not), the recently published schedule reveals that at some times of the day, Finch LRT will be slower than the humble mixed-traffic bus it’s going to replace, averaging 13.5 km/h.

Tramways, rapid transit on a budget?

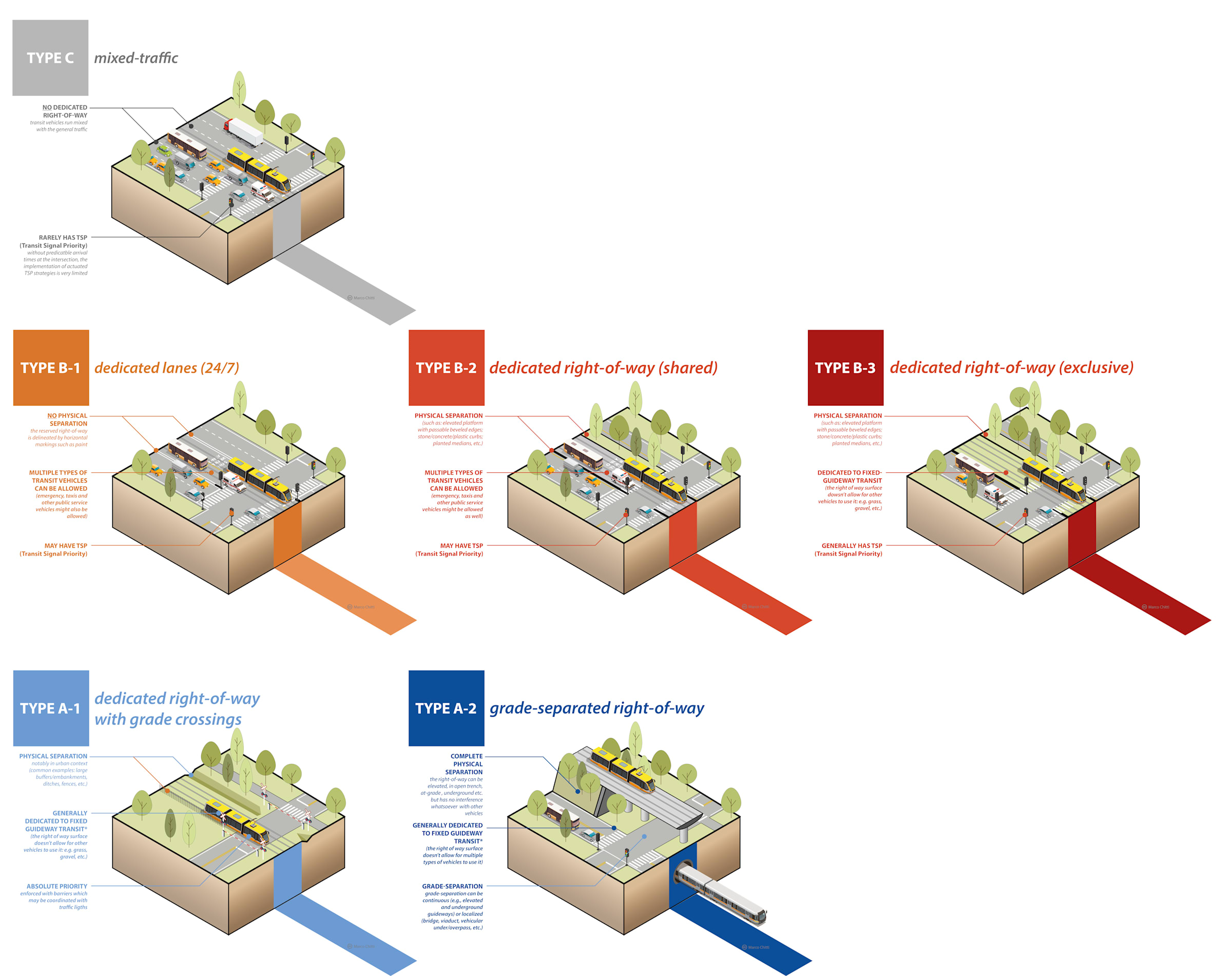

The performances of tramways and urban transit in general, in terms of average speed and regularity, are largely dependent on factors that have little to do with the vehicle itself. The determining factors are the type of right-of-way, stop spacing, the alignment geometry, and the quantity and management of localized conflicts (e.g., intersections). In particular, systems called “trams” can operate on any possible type of right-of-way, from mixed-traffic to fully grade-separated and exclusive alignments.

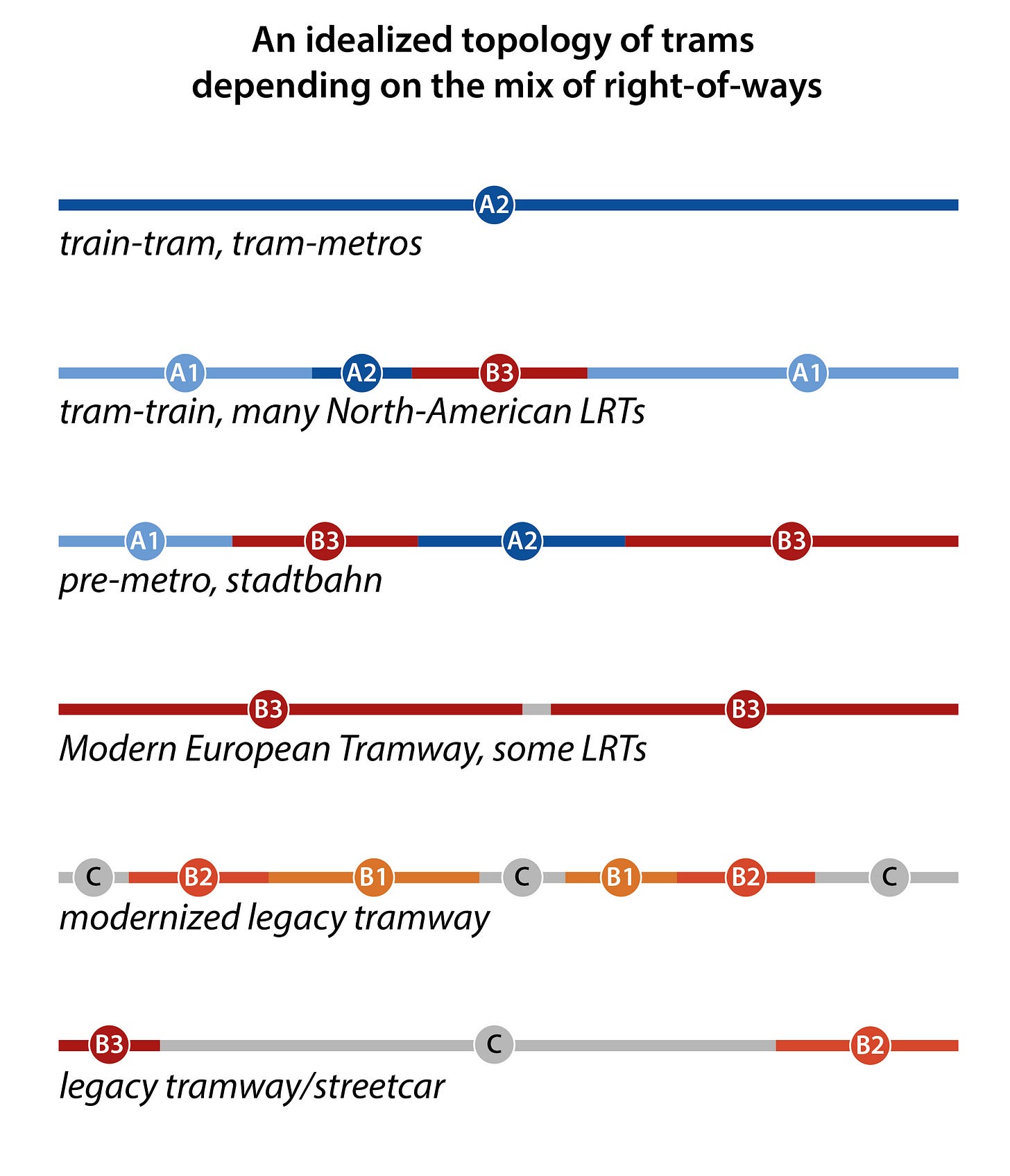

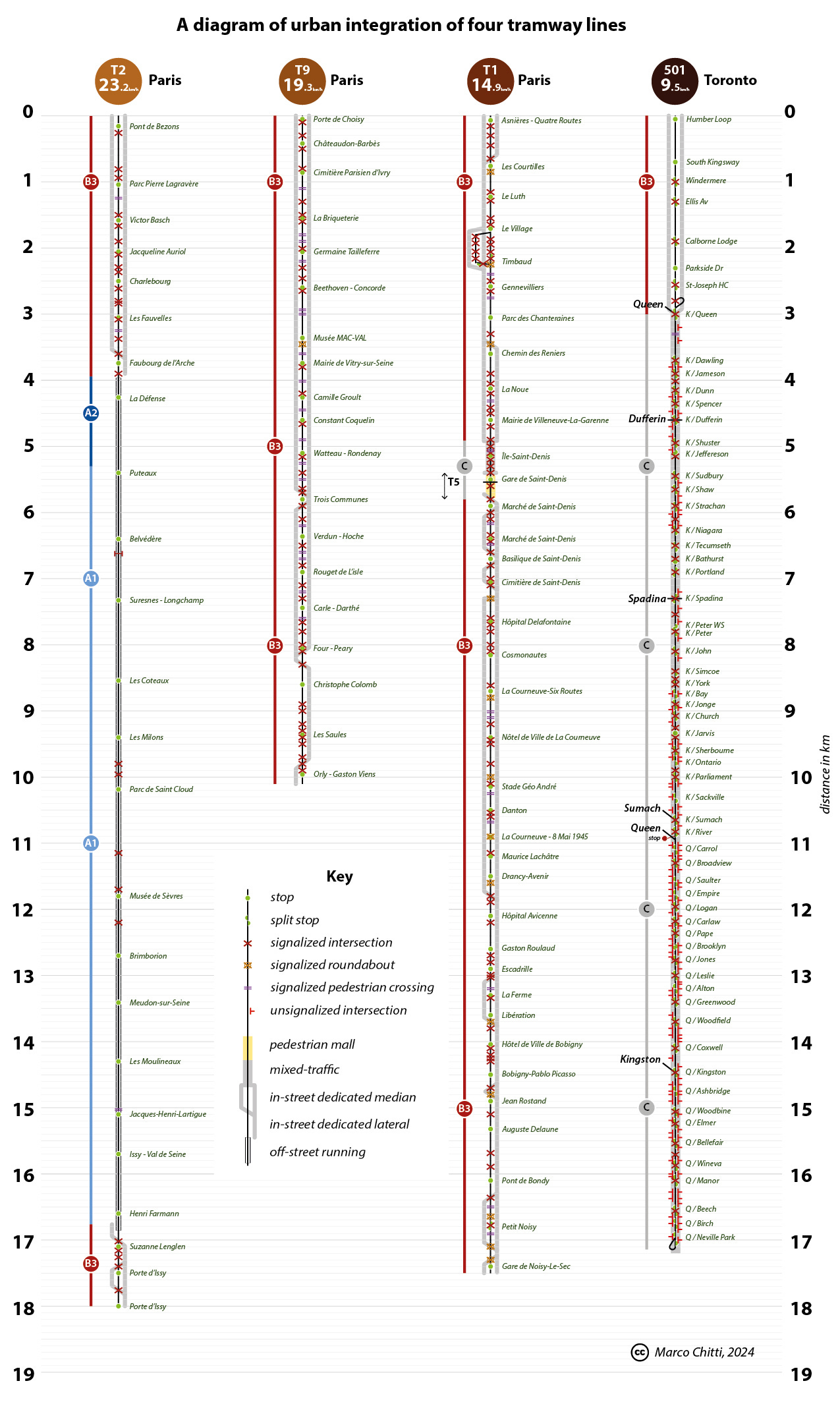

The great terminological confusion surrounding the definition of transit modes stems mainly from how we try to define the mix of right-of-way types a particular rail transit vehicle uses, which is a significant determinant of the quality of service it provides, notably in terms of speed and reliability, which we try to summarize with the term “mode”. Any typological classification is a futile exercise that can quickly wade into a “sex of angels” type of debate, as way too many people interpret it as a prescriptive exercise, rather than a descriptive or heuristic one. “Tramways” and “LRTs” exist on a spectrum that ranges from mostly mixed-traffic operations (type C), such as many unmodernized legacy systems a la Toronto, all the way up to metros cosplaying as trams, such as Ottawa’s LRT and Seville’s metro, operated with tram vehicles. Most tramway systems exist between these two extremes, with as many shades, edge cases and oddities as there are systems under the sun.

But the issue is not just one of right-of-way, but more generally one of urban integration broadly speaking. As soon as a tramway operates in an environment where potential conflicts with other users become the norm rather than the exception (so anything RoW type B and C), that is, an environment where cars, trucks, buses, pedestrians, bikers, etc., regularly cross or encroach on the tracks’ space, the density, distribution and type of points of conflicts makes a difference in terms of performances.

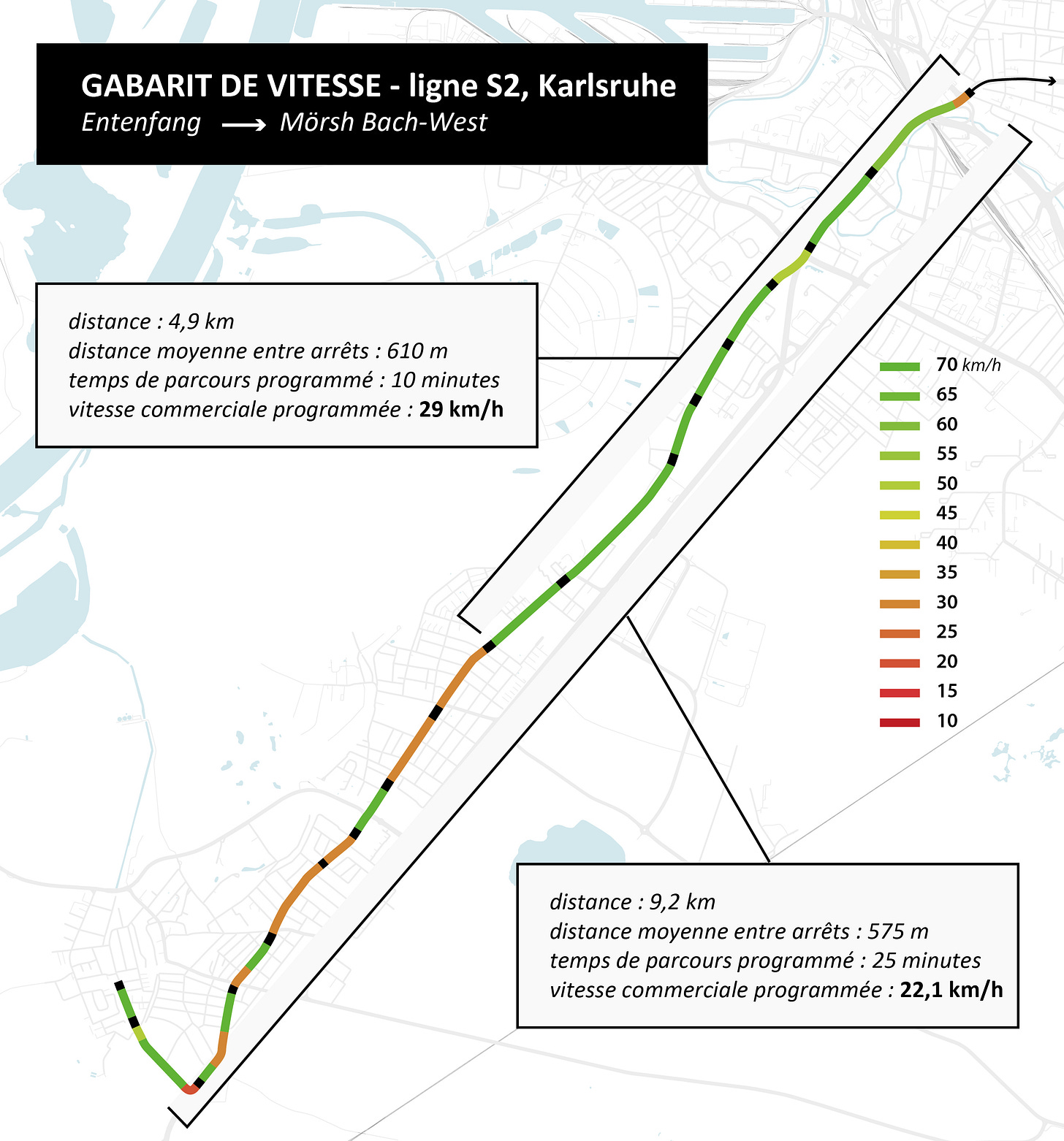

The following diagram shows how two aspects associated with urban integration, such as the type of right-of-way and the points of conflict, notably intersections, broadly correlate with the average scheduled service speed. Tram T2 in Paris, with its long section of type A-1 alignment inherited from a railway line and two segments of type B-3 alignment, reaches a scheduled speed of 23.2 km/h. T9, a quintessential modern French tramway running on grassy medians along a straight suburban boulevard with relatively widely spaced intersections, achieves 19.5 km/h. T1, which follows a more varied alignment, mixing lateral and axial right-of-ways, with many segments cluttered with closely spaced intersections, runs just below 15 km/h on average, despite being more than 95% on a type B-3 dedicated and exclusive right-of-way. Toronto’s 501, with its mostly mixed-traffic alignment (C), its closely spaced intersections, many of which are unsignalized and have poor or non-existent left-turn management, plummets to a scheduled speed of 9.5 km/h.

The Île-de-France is a good case study in itself of what tramways can be, because its tramway (un)network is a mix of very different types of urban integration, resulting in widely different performances. Some trams use former rail alignments for all or part of their length and have wide stop spacing, topping out at 30+ km/h, such as the “express trams” T11, T12, and T13. There are a few hybrid creatures that mix rail-like (types A1 and A2) and in-street dedicated alignments (type B), such as T2 and T4. Finally, there are the more classic modern urban trams with an average speed in the teens. Some reach the 19-20 km/h thanks to straighter alignments (T7, T9 and T10) or short type A-2 grade-separated sections (T6). The more “urban” ones, which run mostly in type B-3 right-of-ways, have closely spaced stops (4-500 m), cross multiple intersections, and sometimes have very curvy alignments, remain in the 14-18 km/h range. Thanks to a generally effective TSP and reasonable speed restrictions compared to what the TTC does, they never reach the abyss of Toronto’s latest gold-plated suburban streetcar, also known as Finch West “LRT”.

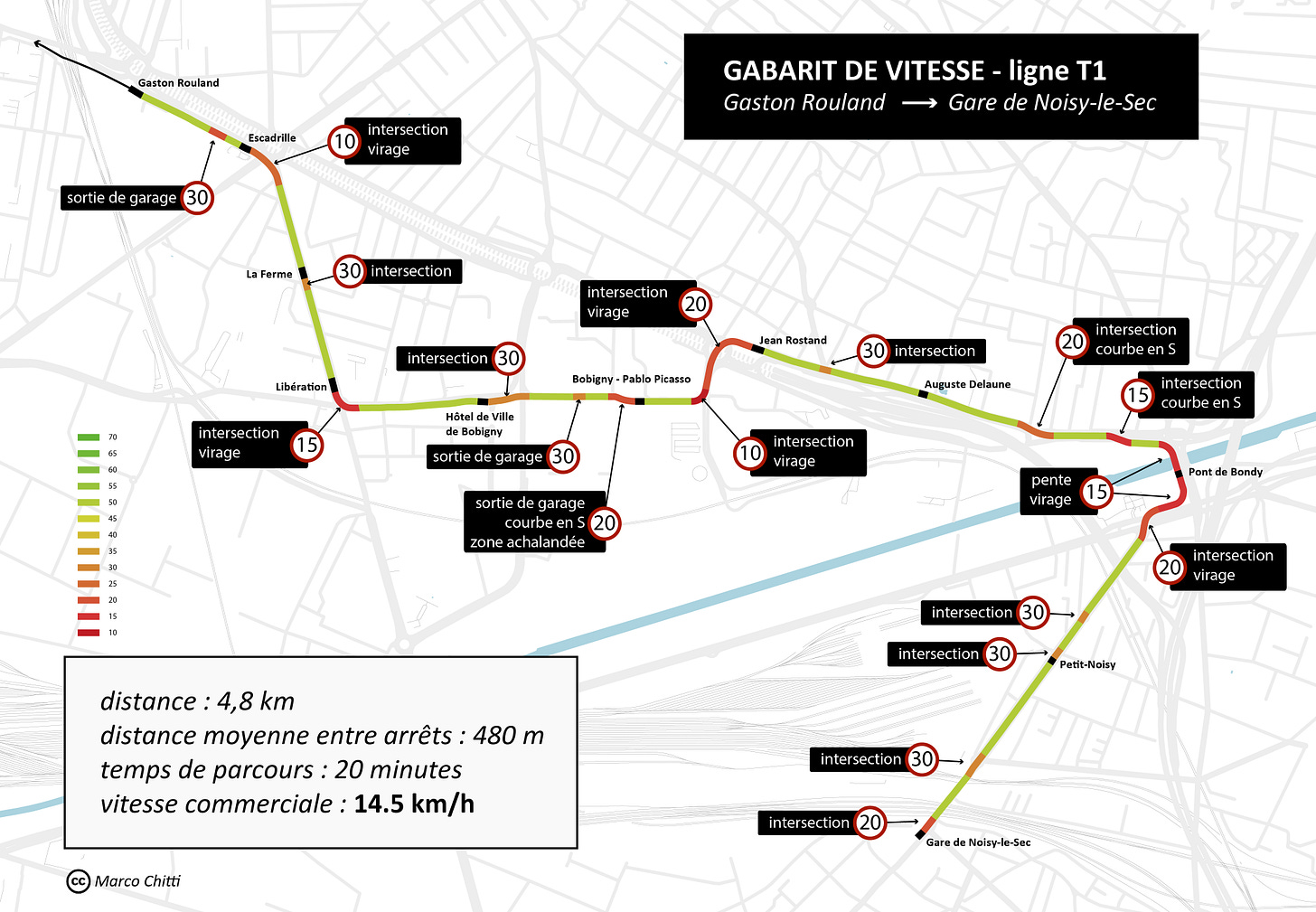

But let’s go into greater detail and examine the “higher permissible speed by segment” (known as “gabarit de vitesse” in French) of a few lines. In the easternmost segment of line T1 in Paris depicted below, we can see how specific circumstances affect the average speed of tramways by capping speed in particular situations, such as tight turns (virages), intersections, driveways when in lateral alignment (sortie de garage), S-shaped curves (courbe en S), steep segments, busy areas (zone achalandée). These frequent slowdowns to 30, 20 or even 10 km/h result in an average scheduled speed of 14.5 km/h, even though the line enjoys absolute priority at signalized intersections, as most modern French trams do.

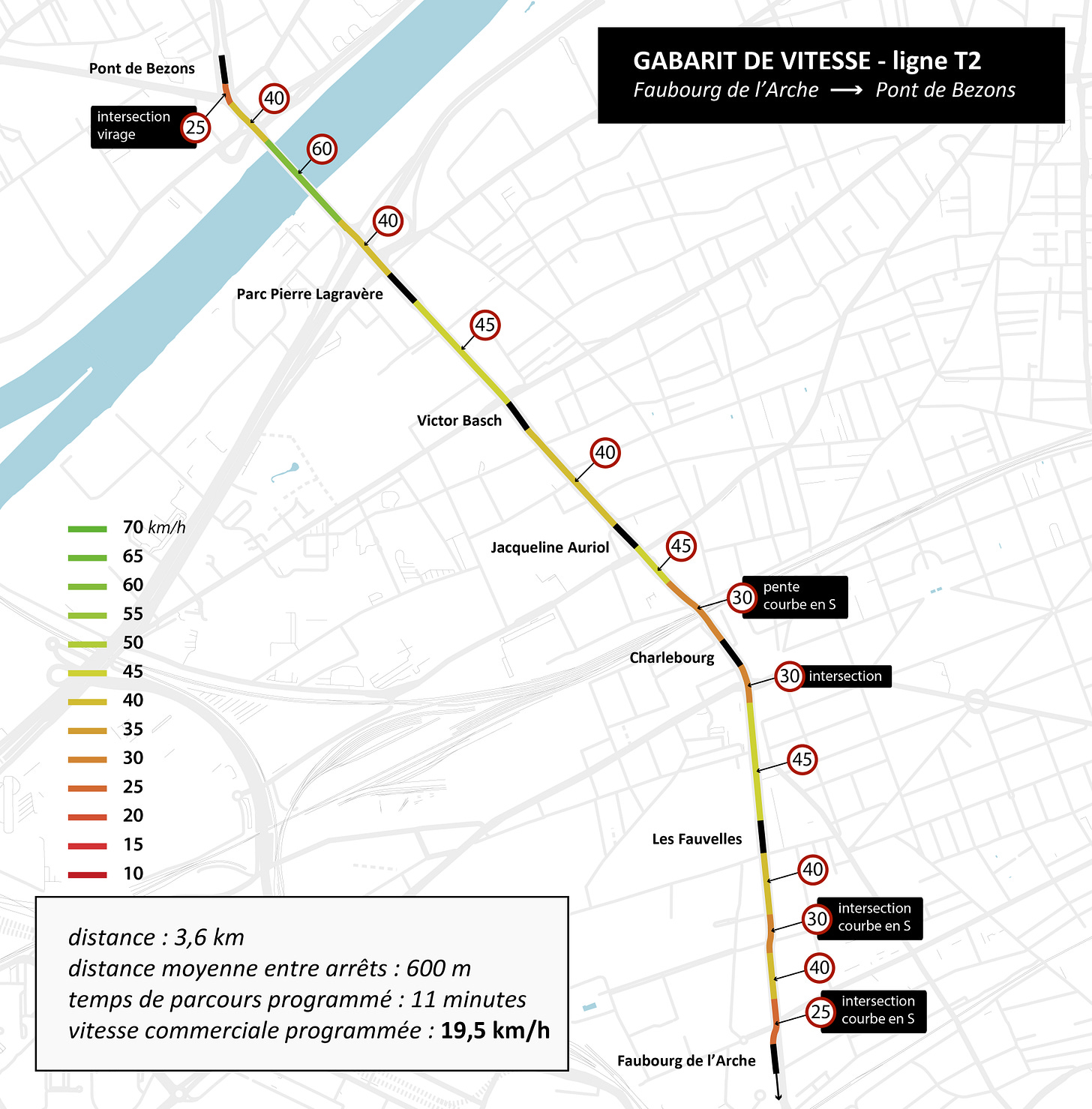

Let’s look at the Northern segment of line T2 now. We see that the line achieves a higher scheduled average speed of 19.5 km/h with a mix of more widely spaced stops and fewer slow zones, as the planners traded localized 30 km/h slow zones at intersections, a staple of post-2000s French tramways, with more even 40-45 km/h speed limits along longer segments (possibly also linked to the will of fine-tuning speed to TSP) to give a smoother ride with less accelerations and decelerations compared to the previous case.

Let’s be realistic

There is growing evidence of an “optimism bias” regarding the attainable performance of tramways or other transit services operating in “type B” right-of-way, pushed by an ill-informed idea diffused in political and planning circles that type B right-of-way and signal priority (a poorly understood problem by laypeople) can yield performances equivalent to a vehicle running in type A right-of-way. In other words, you can have metro performances, but on a budget. Similar to what Bent Flyvbjerg describes for ridership estimates or early cost estimates, there is a tendency in early planning for “strategically misrepresenting” (more or less intentionally) the level of speed performances tramways can achieve.

In the business case, the LRT options for Finch are estimated to reach an average speed of 22 km/h (page 8), well above the currently scheduled 13.5 km/h. In the early 1990s, the expected average speed for Bologna’s planned “metrotranvia” was set at 20-25 km/h, as was common for that kind of project at the time. The current system under construction is expected to average 17.8 km/h (PFTE and Final Design), or as low as 14.5 km/h in more recent documents (Progetto Esecutivo) that incorporate additional speed restrictions required by the fixed-guideway transit regulatory body, ANSFISA. The same happened in Bordeaux, where the initial estimates indicated 21 km/h, while the actual running speed is closer to 18 km/h, and as low as 12 km/h in the city center, with many trips showing no substantial improvement over the pre-existing bus service. In Helsinki, there has long been a target speed of around 25 km/h for LRT in planning documents. However, the realities of the urban environment and the multiple compromises required to achieve other goals, such as safety, urban integration, and coexistence with other modes, have resulted in reduced operational speeds in many recent tramway projects. Only the orbital Jokeri LRT, with its many type A segments, comes close.

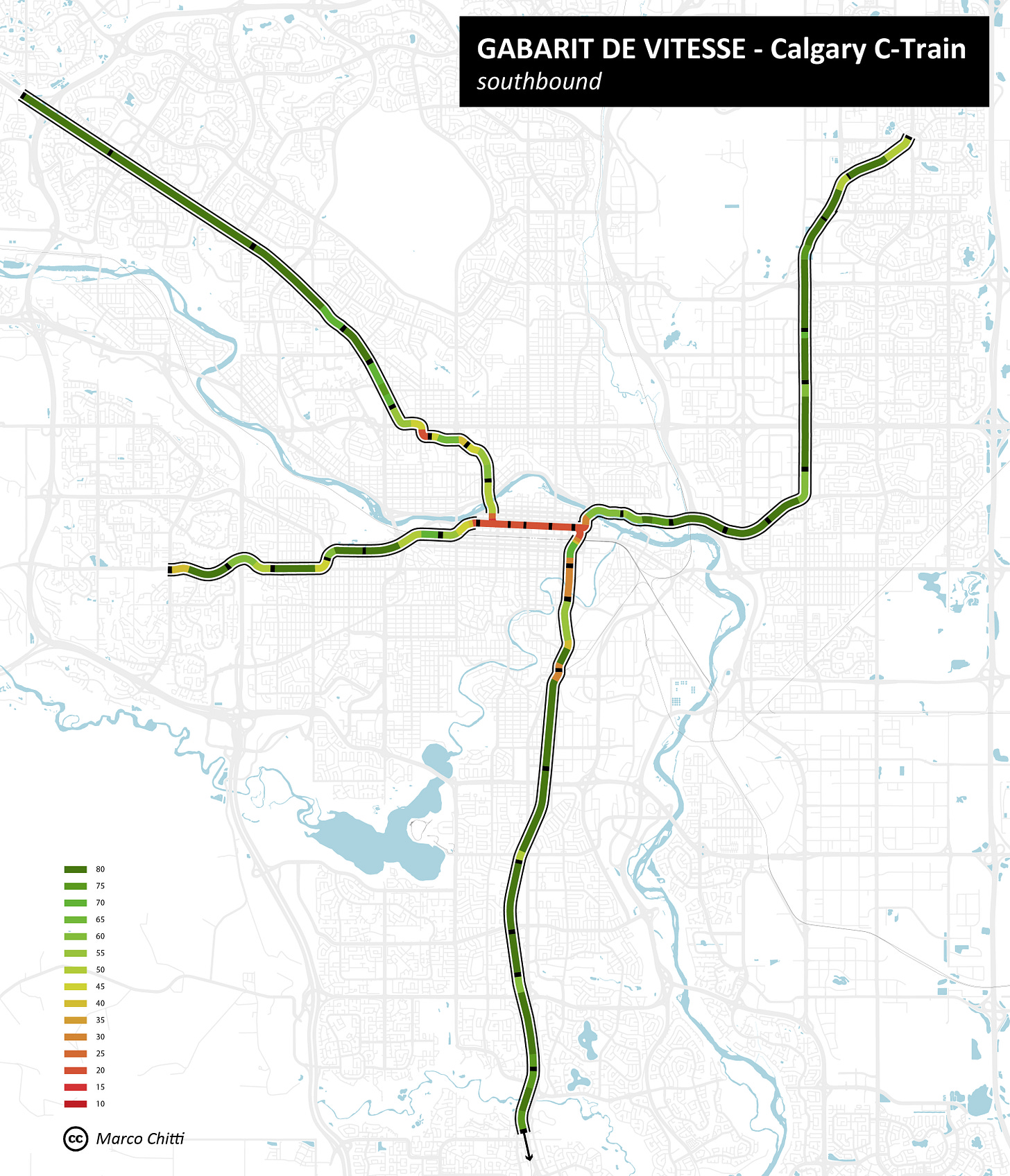

The reality is that type B right-of-way and TSP cannot deliver the same level of performance as grade-separated metros or LRTs. Even more so when your record with TSP is pretty poor, as is the case in Toronto, but in general in North America. Higher performance can indeed be achieved, but it requires erring on the side of type A-1 and A-2 right-of-ways, as first-generation Canadian LRTs did, by installing longer stretches on highway medians or railway corridors with widely spaced stops, as in Calgary. But you can’t have it both nicely integrated and fast. You simply can’t.

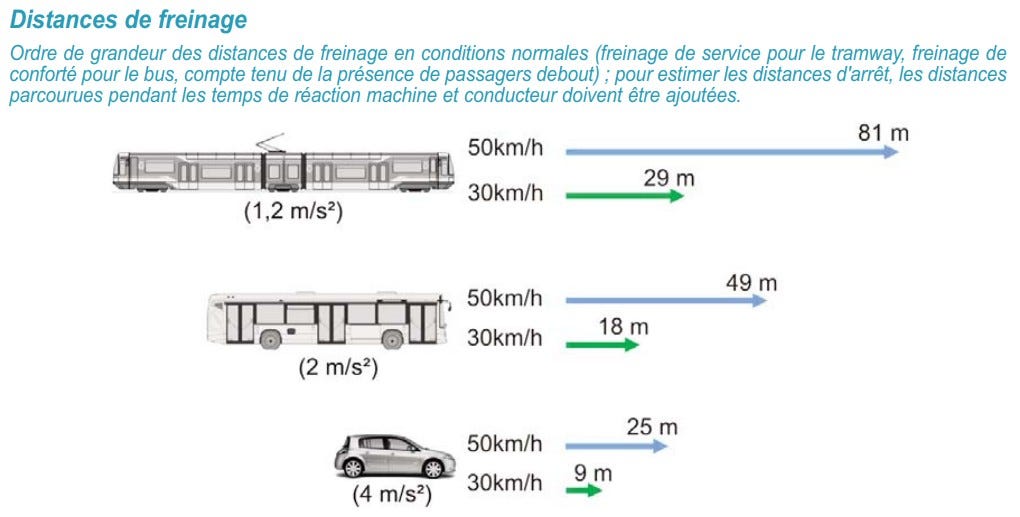

Rail in traffic is at a disadvantage

Finally, it’s important to remember that tramways are severely handicapped compared to buses by being subject to the stricter operating rules of fixed-guideway transit and by the constraints of steel-on-steel bearings and heavy weight, which lengthen breaking distances and make it impossible to avoid a collision by changing direction. Rail vehicles are at a disadvantage when they operate uninsulated from the chaos of the city’s streets.

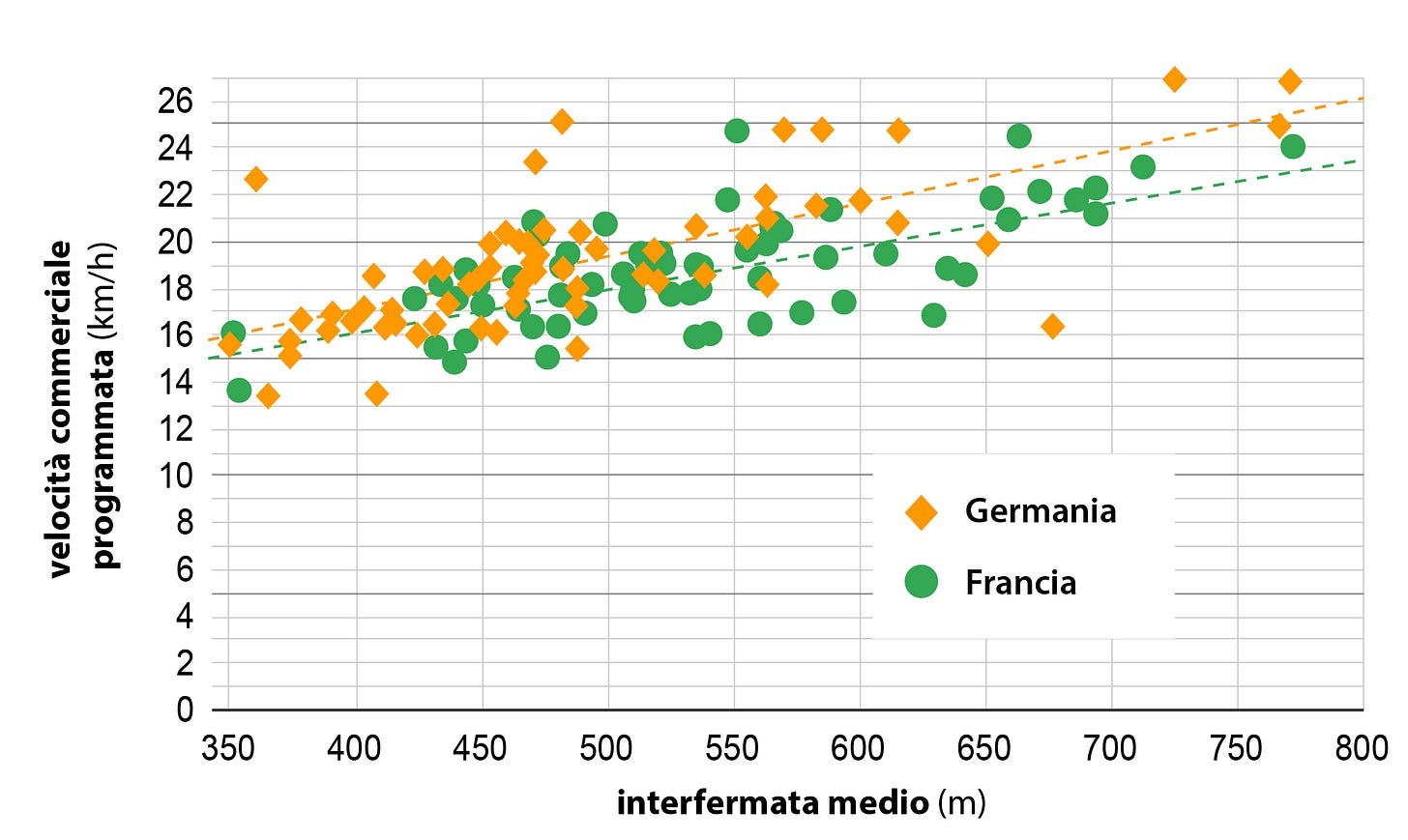

There is a legitimate claim that, in some jurisdictions, safety authorities have been particularly obnoxious in imposing speed limits on tramways, further handicapping them compared to less-regulated buses. This is empirically evident to anyone who has ridden trams on both sides of the Rhine, and it’s also apparent in a quick comparison of tramways’ scheduled speeds in France and Germany: on average, German trams are 1 to 2 km/h faster than French peers with similar stop spacing. While this data isn’t conclusive, as other factors may be at play, it’s a hint that the impression of a more aggressive driving style in central Europe is more than just an impression.

This is also evident in how Germans, for example, tolerate (or used to) higher maximum speeds (up to 70 km/h) in contexts like medians of suburban arterials with widely spaced intersections, like in this example of a section of S2 in Karlsruhe. They generally do not micromanage speed limits at intersections the way the French do, leaving it to drivers to fine-tune their driving style to the circumstances, while respecting the general speed limit of 50 or 70 km/h. However, they limit to lower speeds segments in more urban contexts where collision risks are higher and visibility is worse, as it happens in the more urban segment at the end of S2.

What Trams can do

All else being equal (e.g. efficacy of signal priority and dedicated type B right-of-way), tramways are “just” buses on steroids. That’s not by any means a derogatory definition. They are way better in terms of potential capacity, smoothness of ride, level boarding, and space efficiency (they can fit in narrower right-of-ways than buses, especially on turns). There is a consistent body of literature confirming that there is indeed a “rail effect”, that is, rail-based service attracting more users than an equivalent bus service. For these reasons, tramways have become the preferred mode of many medium-sized and compact European cities, where a 15 km line can stretch from one end to the other of the central built-up area, average trips are relatively short (5-ish km), and buses alone could not handle the demand in terms of capacity and operating costs. Suburban and regional trains (or tram-trains) will handle the longer trips.

There are definitely many situations where a limited capital investment in partial grade-separation, such as a downtown tunnel on busy common stretches or simpler localized grade-separations on complicated traffic nodes, can boost the performance of a tram system, making it suitable for longer trips. Pre-metros and Stadtbahns can perform exceptionally well as the higher-tier transit mode of a relatively large city, balancing speed and coverage and stretching the limits of what trams can do. New-built trams can do a good job to complement higher-order transit on type A right-of-way (metros and trains) in areas of larger cities, for example, in the denser central core (if it exists). There is no prescriptive, specific environment for which trams are “the best mode”, but, as a rule of thumb, I think it’s helpful to think of tramways as buses on steroids rather than 2D metros on a budget.

Build trams. But build them well.

Trams can play a substantive role in the transit ecosystem. They are adapted to both serving as the highest-order transit in medium-sized cities and serving as the complementary mode to metros and trains in larger metro areas. But they cannot replace them, nor are they equivalent. There is no magic trick that can yield type A right-of-way performances while running on cheaper-to-build type B right-of-ways in the middle of an urban environment with its load of potential conflicts. Transit Signal Priority is way trickier to achieve than it appears and can come at the expense not only of cars’ but also of pedestrians’ and bikes’ safety and delays. It’s not a magic trick that suddenly overcomes the problems of time, space and bad behaviour. It comes with a penalty on running times, even when aggressively implemented. No tech trick is as effective as insulating your train from the city’s chaos by putting it in a fully segregated right-of-way, above or below, which comes at a cost.

So, planners, let’s build trams, but let’s do so in the right place and the right way. And please try to understand better the trade-offs and the complexity of urban integration problems. Building a tram through the built environment is not about making easy “Streetmix urbanism”.